LGBTIQ+ Survivors Need Authorities to Conduct Better Investigations into the Torture They Suffered

By Renata Politi, Legal Officer, and Chris Esdaile, Legal Advisor

“I can’t forget when I was raped in the police cell by prisoners,” recalls Kamarah Apollo, a 26-year-old gay activist from Uganda, whose case was featured in one of our recent reports. Disowned by his family and left with no other choice but to engage in sex work for survival, he faced multiple arrests by the police, and endured physical and mental torture at the hands of both civilians and police officers.

Another case which was included in a submission to the UN Human Rights Committee by LGBTIQ organisations in Malawi was the case of Rose, a transgender woman from Malawi, who was assaulted while on her way to church one Sunday morning. Attackers assaulted her and stripped her naked, justifying their actions by claiming she was deviating from societal norms. The assault was recorded and the videos were widely shared on social media platforms. Despite reporting the case to the police, Rose faced further discrimination as the officers insulted her instead of offering assistance. Regrettably, these stories are all too common in various parts of the world, not just in Africa, as shown in the case of one of our clients, Azul Rojas Marín, who was arbitrarily arrested and tortured by police officers in Peru.

These cases share two distressing aspects: victims are tortured or ill-treated due to discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, and the abuses they endure are inadequately investigated or often not investigated at all by national authorities. The lack of adequate investigation prevents access to justice and reparation.

In practice, violence committed against LGBTIQ+ persons frequently amounts to torture, but authorities rarely treat it as such. Impunity for these acts remains alarmingly high. Lack of accountability and insufficient efforts to tackle root causes of discrimination perpetuate this cycle of torture and ill-treatment against LGBTIQ+ persons.

REDRESS and its partners have found that investigations into this discriminatory treatment pose significant barriers to justice and reparation, as it was highlighted in our Unequal Justice report. Too often, survivors of torture who report their cases to national authorities encounter further discrimination, as Rose did. Due to lack of willingness and training, investigations fail to progress or are ineffective.

In some instances, the police themselves are responsible for the abuses, and there is no independent body to whom victims can report the cases. For example, in 2013, Kande (not his real name), an LGBTIQ+ activist in the DRC, was tortured and beaten by police while in detention. He was also beaten and raped by fellow inmates in the presence of an investigator. In the absence of independent bodies to investigate torture committed by the police in the DRC, Kande could not report the incident to a body unconnected to the officers who assaulted him.

Even in rare cases where convictions are secured, authorities rarely investigate whether the torture was motivated by discrimination. Moreover, perpetrators may be convicted of other ordinary crimes instead of being held accountable for torture, as torture may not have been criminalised as a separate offence under national law. Patricia’s case (not her real name) is an example of this. In 2020, Patricia, a lesbian woman from Malawi, was raped by a man who sought to “correct” her sexual orientation. While the perpetrator was eventually convicted of rape, there was no acknowledgement that the abuse she suffered constituted torture, driven by discrimination against her sexual orientation.

The challenges highlighted by these cases are characterised by a widespread lack of awareness among authorities regarding how to investigate torture, and of LGBTIQ+ rights.

To address these pressing issues, REDRESS and its partners, with the support of the law firm Allen & Overy LLP, have published a briefing paper that sets out the relevant international standards concerning the duty to investigate discriminatory torture against LGBTIQ+ persons, and stresses the duty on States to investigate such torture, based on international law, including the UN Convention against Torture. The briefing paper also offers concrete recommendations to improve laws, policies, and practice of investigations into such discriminatory torture.

You can read more about our project, Justice for LGBTIQ+ Torture in Africa, and related publications here.

We are very grateful to our partners, Access Chapter 2 (South Africa), the Centre for the Development of People (Malawi), and the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (Kenya), as well as the law firm Allen & Overy LLP, for their collaboration on this project.

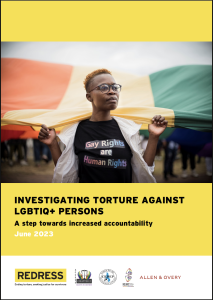

Photo by Anete Lusina.