European Court Accepts Azerbaijan’s Attempts to Resolve LGBTIQ+ Torture Case, Ignoring Victims’ Calls for Effective Reparation

by Chris Esdaile, REDRESS Senior Legal Advisor

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has accepted Azerbaijan’s proposed resolution of a case brought against it by members of the LGBTIQ+ community, despite strong arguments being raised by the victims that the resolution does not deliver adequate reparation for the violations (which in general terms were admitted by Azerbaijan).

REDRESS had submitted a third-party intervention in the case given its relevance to address torture and ill-treatment against LGBTIQ+ individuals, but the Court’s decision has left the issues raised unaddressed. In particular, the case has been concluded without Azerbaijan being required to investigate the allegations made of discriminatory torture and ill-treatment or to take measures to avoid the repetition of the violations.

The case arose as the result of a series of raids in September 2017 by Azerbaijani police in Baku as part of a crackdown on prostitution. The 25 applicants in the case, who belong to the LGBTIQ+ community, were arrested and subjected to ill-treatment and forced medical examinations by police officers and custodial staff while in detention.

The applicants complained that their arrests and detention were unlawful and arbitrary, and that they were identified for arrest on the basis of their sexual orientation and gender identity. Moreover, they alleged that the authorities did not conduct an effective investigation into their ill-treatment and forced medical examination. In October 2017, their complaints were echoed by the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe who demanded formal explanations from the Azerbaijani Minister of Internal Affairs. They were also echoed group of UN experts who published a statement calling the Azerbaijani authorities to “investigate promptly and thoroughly all allegations of torture and ill-treatment and ensure that perpetrators are prosecuted and, if convicted, punished with adequate sanctions”.

In 2018, the victims lodged their applications with the ECtHR alleging multiple violations of their European Convention rights, in particular Articles 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment), 5 (right to liberty and security), 6 (right to a fair trial), 8 (right to respect for private life) and 14 (prohibition of discrimination).

In 2019, REDRESS submitted a third-party intervention along with ILGA-Europe (the European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association) and Civil Rights Defenders. The submission argued the following:

- States have a heightened obligation to protect vulnerable persons and certain minority or marginalized individuals or populations especially at risk of torture – given the vulnerability of LGBTIQ+ persons to discriminatory violence, the discriminatory use of mental or physical violence is an important indicator that an act constitutes torture;

- the forced medical examination of detainees may amount to a breach of Articles 3 and 8 of the Convention if the individual subjected to the medical examination is particularly vulnerable and the examination is carried out with discriminatory motives;

- States have specific obligations to investigate adequately allegations of ill-treatment and torture with discriminatory elements;

- Azerbaijan’s hate crime law does not include gender identity and sexual orientation as protected grounds, and authorities there are generally hostile towards LGBTIQ+ persons – both are factors which contribute to heightening the vulnerability of individuals belonging to the LGBTIQ+ community.

After the parties failed to reach a negotiated settlement of the case , the government proposed making a ‘unilateral declaration’ – something they are entitled to do under the ECtHR’s rules – and on this basis asked the Court to bring the cases to an end. The unilateral declaration proposed included a general admission that Azerbaijan had violated the Convention, and an offer to pay compensation. The victims disagreed with this proposal on the basis that they wanted more specificity over the precise violations being admitted, that the compensation offered was inadequate, that the government had not promised to investigate the violations alleged, and that, given that this was the first such case against Azerbaijan regarding the rights of LGBITQ+ individuals, it was important and merited full consideration by the Court.

However, on 19 March 2024, the Court issued a short judgment confirming that the cases should all be ‘struck out’ on the basis that the proposed universal declaration was sufficient, and that “respect for human rights as defined in the Convention… does not require it to continue the examination of the applications”. The substantive elements of the applicants’ case, and the details of our intervention, were not addressed by the Court in its judgment.

We are concerned at the way the ECtHR in this case has interpreted its responsibility to offer remedies to alleged victims of torture and ill-treatment who have brought their cases alleging violations of Article 3 of the European Convention.

The Court has repeatedly emphasised in its case law that the payment of compensation is not sufficient to remedy a breach of Article 3, but that such a measure must be combined with an effective investigation capable of leading to the identification and punishment of those responsible (Gäfgen v Germany, at [115] – [116], [119]). The Court justified such an approach by noting:

“…if the authorities could confine their reaction to incidents of willful ill-treatment by State agents to the mere payment of compensation, while not doing enough to prosecute and punish those responsible, it would be possible in some cases for agents of the State to abuse the rights of those within their control with virtual impunity, and the general legal prohibition of torture and inhuman and degrading treatment, despite its fundamental importance, would be ineffective in practice…” [119].

An effective and meaningful investigation is especially important when the alleged torture involves discrimination against LGBTIQ+ individuals which cannot otherwise be unmasked (Identoba and Other v Georgia, at [67] and [80]).

Unfortunately, in A v Azerbaijan, the Court has accepted a unilateral declaration in a case involving Article 3, despite the fact that the declaration does not include an admission reflecting the gravity of the events, or an undertaking to investigate such violations, or a commitment to take measures to prevent similar violations in the future. In such cases, even where there are clear allegations of discriminatory torture, these allegations will remain uninvestigated. This is despite the fact that the Court has the power to reject unilateral declarations on the basis that “respect for human rights” requires it to continue its examination of the case (Jeronovics v. Latvia, at [64]).

While REDRESS would generally support the Court’s efforts to get on top of its caseload by adopting measures which reduce the number of cases which it has to consider in full such measures should not be taken at the expense of limiting the scope of protection offered by the European Convention and the rights of victims to seek an effective remedy before the ECtHR. In cases like this which are central to the fundamental rights enshrined in the European Convention, the Court could and should be exercising its power to reject unilateral declarations which do not include measures sufficient to remedy breaches of Article 3. Otherwise, the rule of law is undermined and the purpose and spirit of the Convention is obstructed.

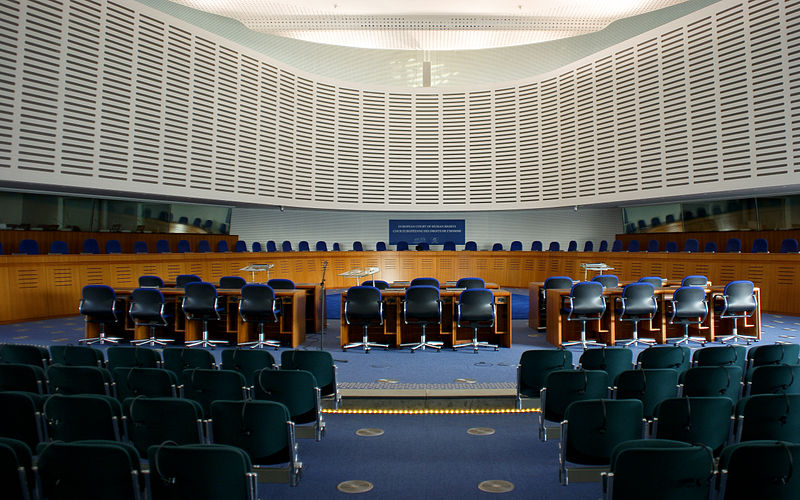

Photo: CherryX per Wikimedia Commons